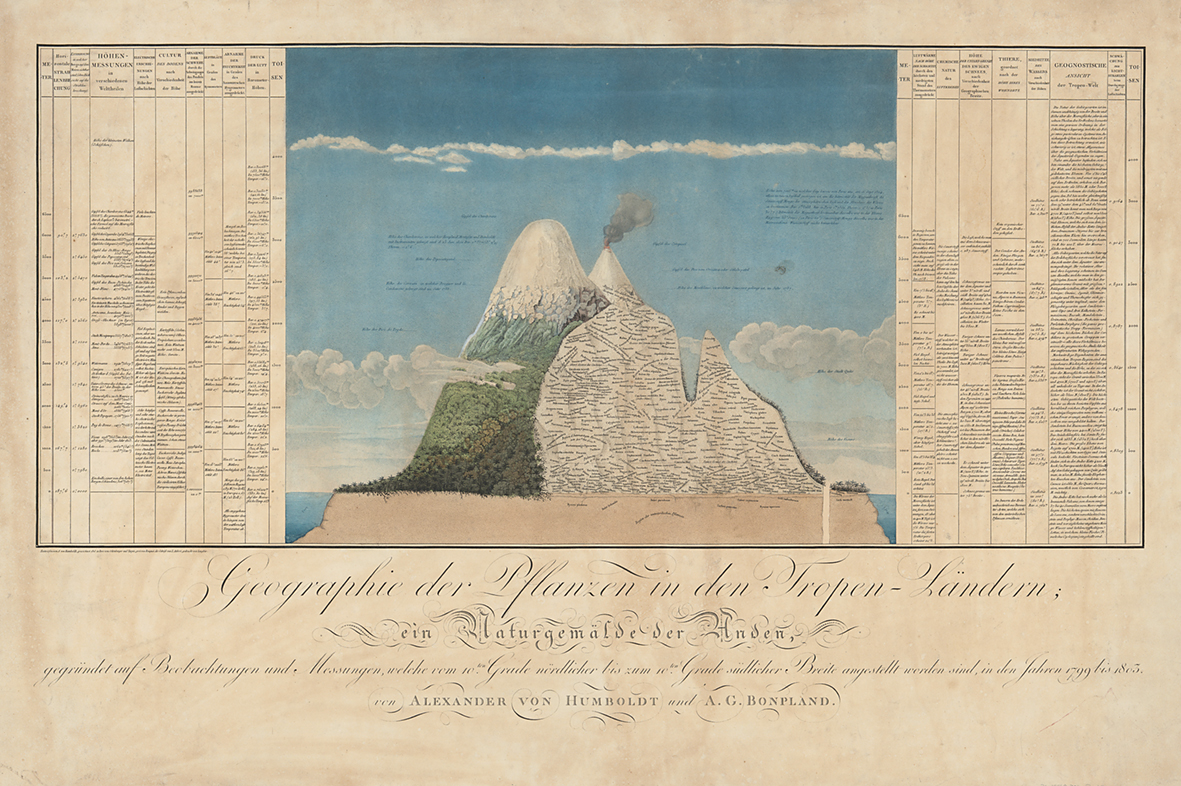

The biogeographical concept of tropical verticality has been associated with Chimborazo thanks to the worldwide circulation of images of the volcano produced by Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland. Contrary to common belief however, the concept was not invented or discovered by Humboldt. The notion that ecological diversity or plenitude depended upon altitude rather than latitude was first articulated by early modern Hispanic natural historians in the Andes. Intrepid Jesuit naturalists such as José de Acosta discovered that climate was as much a function of elevation and microclimate as it was of latitude. The first author to make an explicit connection between slope and tropical diversity was probably the Peruvian Creole Antonio de León Pinelo (1590– 1660), who argued that of all places in the world, only the Andes could have reached the middle region of the sphere of air, where corruption and the transformation of the elements were considerably retarded, thus allowing the eternal conditions of Paradise to persist. Later, Carolus Linnaeus (1707–1778) deployed the ancient image of Paradise as an equatorial mountain to explain biodistribution and secure support for state-building projects in Europe. In this cameralist or statist vein, Humboldt’s field research practice connected underground (mining) and over-ground (botanical) mapping of natural resources, producing a penetrating vision of entire countries as mines and agricultural zones that could be exploited by foreign interests.

HUMBOLDT’S CHIMBORAZO

A. von Humboldt and A.G. Bonpland, Geographie der Pflanzen in den Tropenländern, ein Naturgemälde der Anden (courtesy of Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Kartenabteilung).

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra and Mark Thurner

Further reading

- Anthony, P. (2018) ‘Mining as the working world of Alexander von Humboldt’s plant geography and vertical cartography’, Isis, 109 (1): 28–55.

- Cañizares-Esguerra, J. (2006) Nature, Empire, and Nation: Explorations of the History of Science in the Iberian World (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press).

- Cañizares-Esguerra, J. (2004) ‘How derivative was Humboldt? Microcosmic nature narratives in early modern Spanish America and the (other) origins of Humboldt’s ecological ideas’, in Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World, edited by L. Schiebinger and C. Swan, 148–65 (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press).

- Cañizares-Esguerra, J. (2001) How to Write the History of the New World: Histories, Epistemologies, and Identities in the Eighteenth- Century Atlantic World (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press).

- Masuda, S., I. Shimada, and C. Morris (eds.) (1985) Andean Ecology and Civilization: An Interdisciplinary Perspective on Andean Ecological Complementarity (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press).

- Murra, J.V. (1956) The Economic Organization of the Inca State (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press).

- Thurner, M. (2011) History’s Peru: The Poetics of Colonial and Postcolonial Historiography (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida).