The Royal Cabinet of Natural History, established in Madrid in 1776, is remarkable not only for its Creole origins but also for its haunting afterlife. The cabinet was based on the collection of the Guayaquil-born Creole polymath, Pedro Franco Dávila. Franco Dávila’s collection was particularly rich in shells, minerals and fossils. The cabinet also held artefacts of human industry, including paintings by Murillo and Bosch, gilded tobacco boxes, microscopes, weapons, ethnographic objects, Egyptian bronzes, chinaware, and Caribbean idols. The gaps in Franco Dávila’s curious collection were soon filled by new items remitted from the Indies. The upstairs apartment of the Goyeneche Palace was no longer enough. Charles III commissioned architect Juan de Villanueva to design a magnificent home for the expanding Royal Cabinet, along with a chemistry laboratory, a cabinet of Instruments and Machines, and a new Academy of Sciences. By a twist of fate, however, Villanueva’s natural history museum became the Prado art museum. Napoleon’s invading army occupied Villanueva’s edifice. Meanwhile, Napoleon’s Corsican born brother Joseph Bonaparte was proclaimed José I of Spain and the Indies. King José I created by decree a new Museum of Painting, in part to house the art removed by French troops from Spain’s royal palaces, churches and monasteries, including El Escorial. With the restoration of Ferdinand VII, the Bonapartist painting museum was renamed Museo Fernandino. In 1819 Ferdinand VII opened the Royal Museum of Painting and Sculpture in Villanueva’s refitted palace, today known as the Prado Museum. Meanwhile, the Royal Cabinet survived in the Goyeneche Palace, where it had its ups and downs. After years in storage, it was installed in what is today the National Museum of Natural Sciences (MNCN). Today, all the major museums of Madrid trace their origins to Franco Dávila’s cabinet.

Royal Cabinet of Natural History

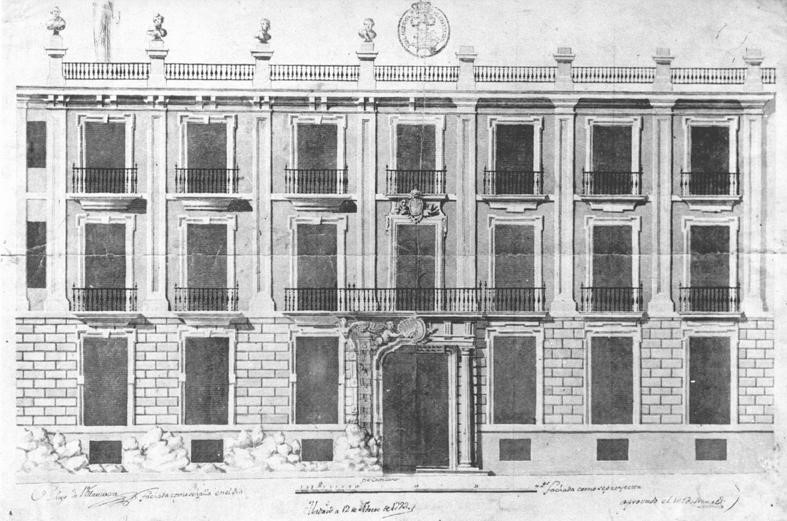

Façade of Goyeneche Palace, premises of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando and the Royal Cabinet of Natural History (photographic reproduction courtesy of CSIC).

Juan Pimentel and Mark Thurner

Further reading

- Barras de Aragón, F. (1912) ‘Una historia del Perú contenida en un cuadro al óleo de 1799’, Boletín de la Real Sociedad Española de Historia Natural, vol. 11, 224–85.

- Bleichmar, D. (2011) ‘Seeing Peruvian nature, up close and from afar’, Res 59/69, 82–95.

- Lequanda, J.I., and L. Thiébaut (1799) Quadro de Historia Natural, Civil y Geográfica del Reyno del Perú (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid). https://artsandculture. google.com/asset/quadro-de-historia-natural- civil-y-geogr%C3%A1fica-del-reyno-del- per%C3%BA-jos%C3%A9-ignacio-de- lequanda/igE86USP5Q1cYg?hl=es

- Peralta, V. (2015) ‘La exportación de la Ilustración Peruana. De Alejandro Malaspina a José Ignacio de Lecanda, 1794–1799’, Colonial Latin American Review, 24 (1): 36–59.

- Pimentel, J. (2003) Testigos del mundo: ciencia, literatura y viajes en la ilustración (Madrid: Marcial Pons).

- del Pino, F. (ed.) (2014) El quadro de historia del Perú (1799), un texto ilustrado del Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (Lima: Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina).

- Sánchez-Valero, M., J.S. Almazán, J. Muñoz, and Yagüe (2009) El gabinete perdido: Pedro Franco Dávila y la historia natural del Siglo de las Luces (Madrid: CSIC).

- Thurner, M. (2011) History’s Peru: The Poetics of Colonial and Postcolonial Historiography (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida).

- — (2018) ‘Historia secreta de la ilustración. O morir en Cádiz’, Revista Hispano Americana, vol. 8, 1–8.