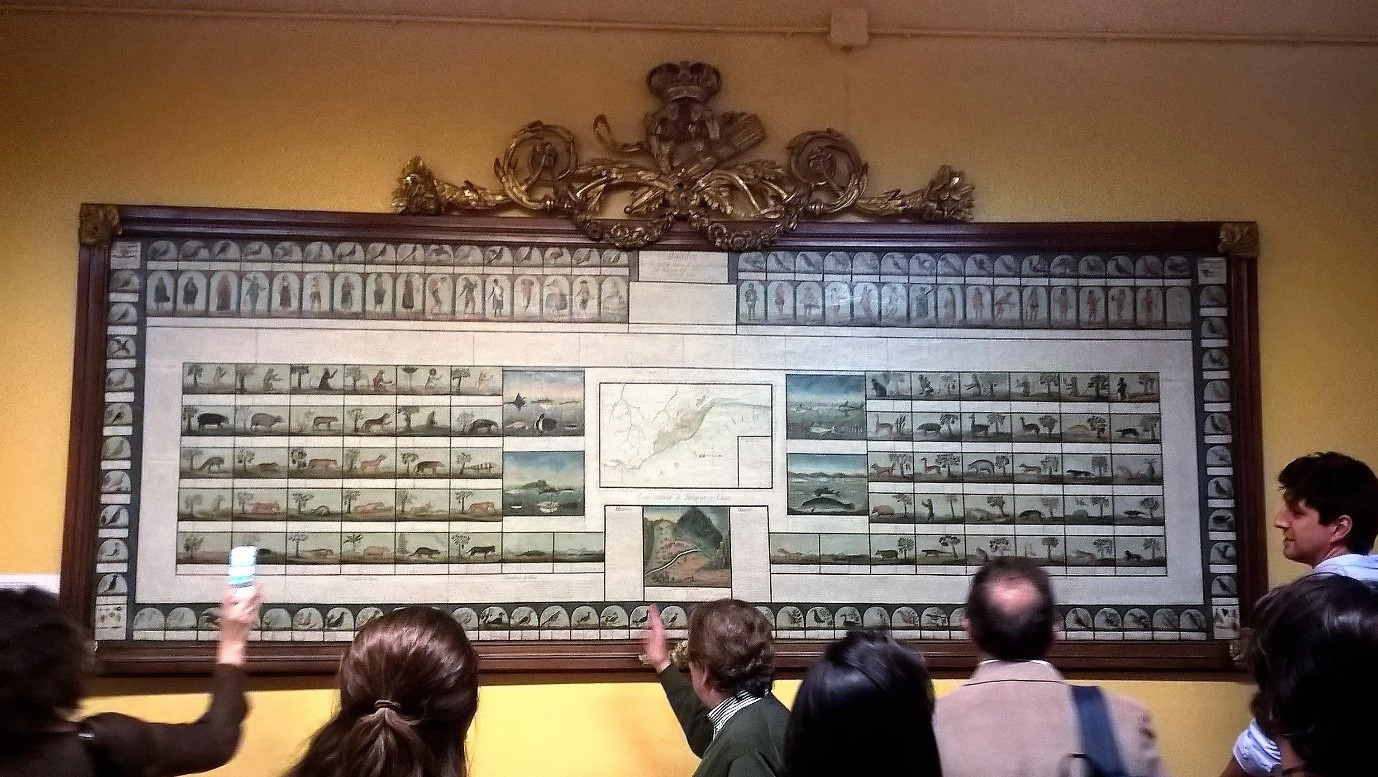

The Quadro’s primary author was José Ignacio de Lequanda (Vizcaya 1748 – Cadiz 1800). The illustrations were made by Louis Thiebaut from many sources, including the so-called Trujillo del Perú Codex (1782–85) and the Malaspina Expedition (1789-1794). Lequanda resided for most of his productive life in Lima, where he contributed to the Mercurio Peruano (1791–94). The material of the Quadro is oil on canvas but it is distinguished by its unusual dimensions (331 cm × 118 cm) and composition: 195 scenes with 381 figures surrounded by explanatory text. In addition, the framed canvas is crowned and gilded with twin cornucopias graced by a sheaf of arrows, symbolising the bounty or ‘treasure’ of the New World under Hispanic Monarchy. The two central geographical images (an east-up map of central Peru, and below it a profile view of the rich mines at Hualgayoc) form an axis that represents the new economic centre of 18th-century Peru, which had shifted from Potosí to the region adjacent to Lima. The central region united three major ecological and productive zones. In the Quadro, this vertical economic geography is represented by the unfolding of a concentric sequence of niches populated by fishes and amphibians, small and large quadrupeds, simians, and humans. The latter is divided in two classes, ‘civilised’ (or coastal and highland) and ‘savage’ (or Amazonian), with each composed of 16 ‘nations’. Birds occupy the perimeter of the Quadro, seemingly lifting the entire canvas on their wings. In a word, the Quadro is a tableau that reveals in a synoptic visual field what today we call ‘biodiversity’ but which in enlightened circles of the times was called ‘the idea of Peru.’ This ‘idea’ held that Peru was a mirror of the universe and the crown jewel of Hispanic Empire.

Quadro del Peru

El Quadro de Historia Natural, Civil y Geográfica del Reyno del Perú, año de 1799 (courtesy of the National Museum of Natural Sciences, Madrid). A high-quality image of the Quadro is available for viewing on the Google Arts and Culture platform: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/quadro-de-historia-natural-civil-y-geogr%C3%A1fica-del-reyno-del-per%C3%BA-jos%C3%A9- ignacio-de-lequanda/igE86USP5Q1cYg?hl=es

Mark Thurner and Juan Pimentel

Further reading

- Barras de Aragón, F. (1912) ‘Una historia del Perú contenida en un cuadro al óleo de 1799’, Boletín de la Real Sociedad Española de Historia Natural, vol. 11, 224–85.

- Bleichmar, D. (2011) ‘Seeing Peruvian nature, up close and from afar’, Res 59/69, 82–95.

- Lequanda, J.I., and L. Thiébaut (1799) Quadro de Historia Natural, Civil y Geográfica del Reyno del Perú (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid). https://artsandculture. google.com/asset/quadro-de-historia-natural- civil-y-geogr%C3%A1fica-del-reyno-del- per%C3%BA-jos%C3%A9-ignacio-de- lequanda/igE86USP5Q1cYg?hl=es

- Peralta, V. (2015) ‘La exportación de la Ilustración Peruana. De Alejandro Malaspina a José Ignacio de Lecanda, 1794–1799’, Colonial Latin American Review, 24 (1): 36–59.

- Pimentel, J. (2003) Testigos del mundo: ciencia, literatura y viajes en la ilustración (Madrid: Marcial Pons).

- del Pino, F. (ed.) (2014) El quadro de historia del Perú (1799), un texto ilustrado del Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (Lima: Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina).

- Sánchez-Valero, M., J.S. Almazán, J. Muñoz, and Yagüe (2009) El gabinete perdido: Pedro Franco Dávila y la historia natural del Siglo de las Luces (Madrid: CSIC).

- Thurner, M. (2011) History’s Peru: The Poetics of Colonial and Postcolonial Historiography (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida).

- (2018) ‘Historia secreta de la ilustración. O morir en Cádiz’, Revista Hispano Americana, vol. 8, 1–8.