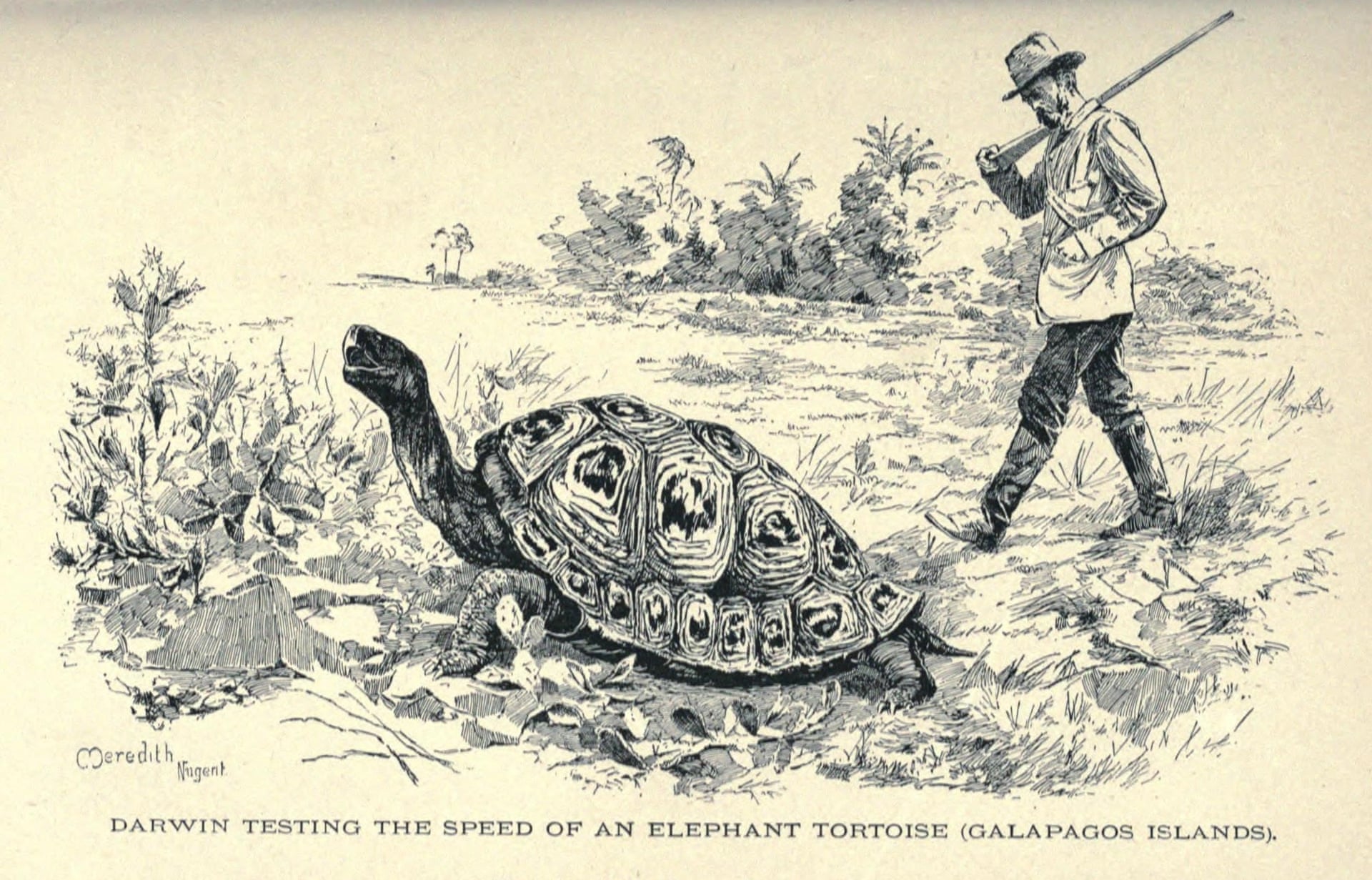

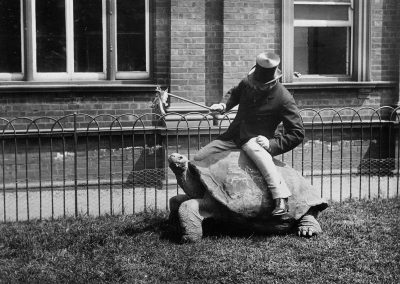

On a sunny day in October 1835, a 26-year-old Charles Darwin hiked from the parched coast of Santiago Island in the Galápagos archipelago to the island’s green, damp highlands. After a long walk, he sat in the shade and watched the island’s giant tortoises as they ambled along broad roads that had been trodden by their elephant-like feet over countless generations. He timed their gait, measured their carapaces and tried to lift them. Finding he could not, he climbed on their backs as they trudged along. The acting vice-governor, a Norwegian mercenary named Nicholas Lawson, remarked to Darwin that he could ‘with certainty tell from which island any [tortoise] was brought’. On small, dry islands, the tortoises were smaller. On larger, higher islands like Floreana and Santiago, where volcanic calderas are often enshrouded in misty clouds, the tortoises were much larger when full grown and their carapaces were dome-shaped. While in the Galápagos, Darwin failed to see the importance of what Lawson had said: ‘I did not for some time pay sufficient attention to this statement’, Darwin lamented back in England years later when he began considering the evolutionary significance of the giant tortoises and other Galápagos animals. When Darwin was in the Galápagos, he was not yet thinking about evolution. Although he made notes about the tortoises’ behaviour, gait, hearing and size, he did not make collections of the animals, as he did with island birds, plants, rocks, lizards and insects. Instead, he ate them.