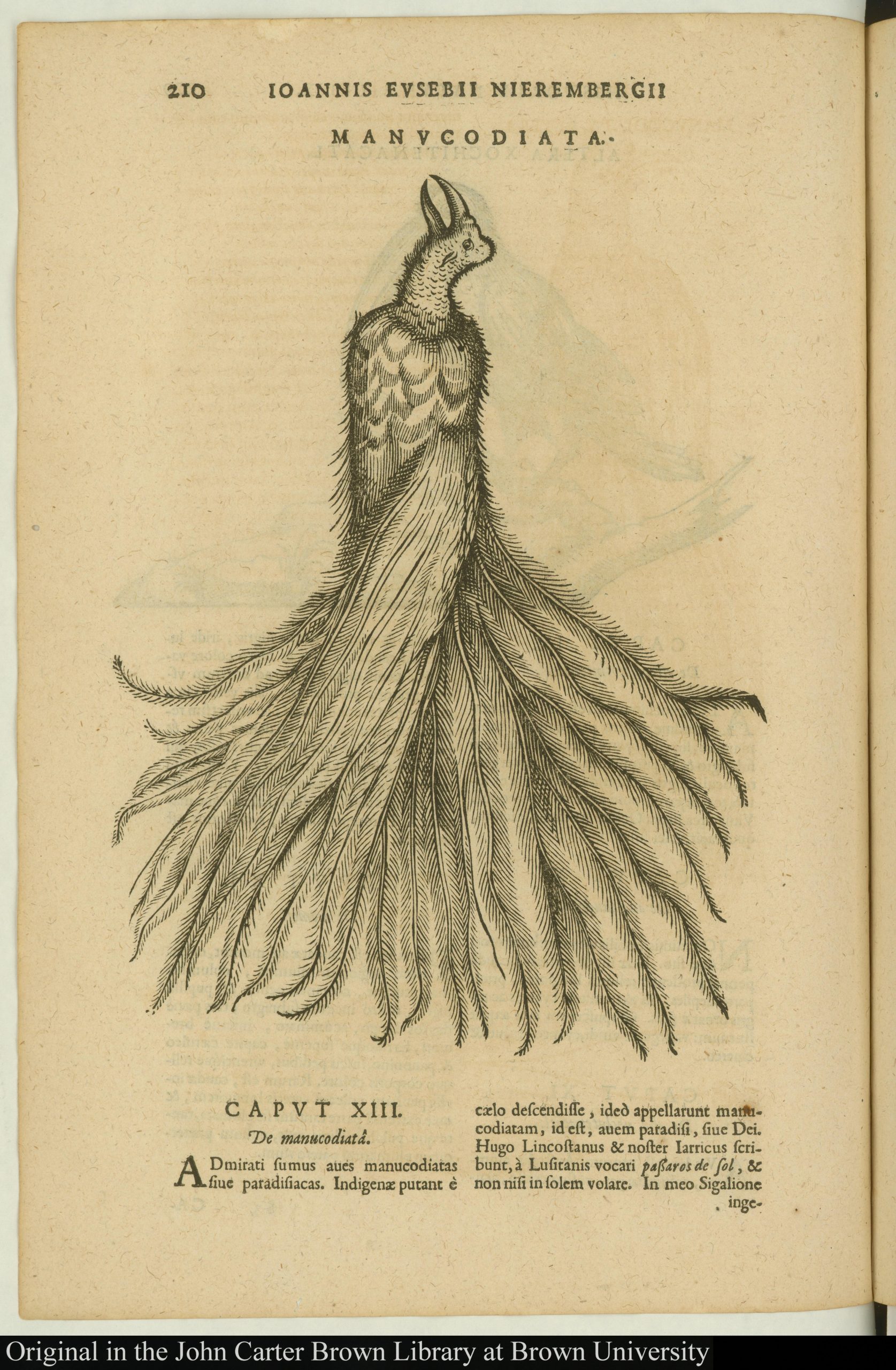

In the early decades of the 16th century, the Bird of Paradise – native to New Guinea and the Moluccas archipelago – was considered a rarity. Travel accounts soon gave rise to the legend that the bird lacked feet and thus spent its lifetime aloft in permanent flight. One of the earliest and most remarkable descriptions of the bird appears in the revised and expanded version of the first part of the General and Natural History of the Indies by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo (1478–1557). Oviedo begins his account of this bird skin by noting his inability to express in words the beauty of the thing. He then proceeds to provide an exhaustive written description of a specimen in his possession. First Oviedo establishes comparisons with more familiar European birds. On the contested issue of the bird’s feet, he states that the bird does not seem to have any, although he admits to having felt with his fingers two little stumps where the feet should have been. Near the end, Oviedo reflects on the ornamental use of the bird and its association with majesty and power. He notes Urdaneta’s account of the value of the bird for Moluccan elites, who wore it as a headdress symbol of prestige. He suggests that the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, would do well to wear one of these birds as a symbol of his magnificence and power. Oviedo’s description testifies to the bird’s status as a global perpetuum mobile of trade, prestige and knowledge.