Astrid Torres

The virtual space has been configured as another side of the public space, which means that violent practices are also reproduced there. Physical dynamics are transferred to the virtual, giving greater freedom to position agendas, but hate speech also increases. If you ask me, what does a human rights content creator do? I would say that he is someone who disputes the virtual territory to position an agenda that questions the forms of oppression while avoiding the haters.

The simplest definition of “hater” is a hater: a person who, through social networks, dedicates themselves to attacking and denigrating others for being against their ideas. In this text I particularly reflect on my experience with haters on Tiktok, a space where I create content through the Roja Post project with @rojaindpomita.

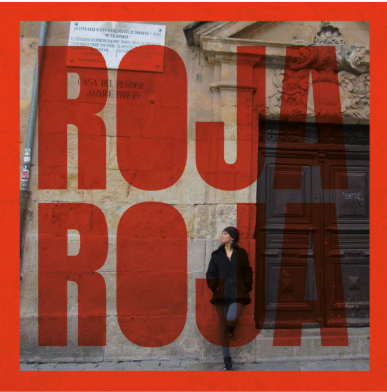

Tiktok in recent years has become a direct competitor to Meta and Google. More and more media and politicians are opening an account on this social network because it is a platform with a constant flow of information. The perfect place to plant ideas. In this context, the identity I designed for Tiktok reflects a way of thinking: red, for a clear trend of progressivism; and, untamed, by a particular rebellion against the unjust social imaginaries that have been imposed through control institutions such as the media.

The path of content creation begins with defining the identity of our space, the agenda and a lot of patience to navigate the algorithm that requires constant work. Positioning a voice on networks implies WORK, often unpaid. Although it may seem like an individual job, the creation of content on human rights is collective like the agenda that is intended to be placed, since support and learning networks are formed. To give an example, I belong to the Creadoras Camp community, a feminist content creation school that, after the training stage, brings together content creators from across the region in a network where collaborations, advice, and content support can arise. published.

This network is also a safe and supportive space, since the positioning of agendas related to feminism or inequalities always generates comments from haters because the status quo is questioned. And this increases when it is a woman who speaks, since our society is structurally sexist. In this sense, beauty has historically been a system of oppression for women and our bodies have been under constant scrutiny. So, it is not surprising that when there are no arguments the point is made at our bodies.

“Prepaids don’t talk about politics”, “Who is your dentist not to go?” «Horse teeth are a disease, I only understood that», «Go study it, she’s only half pretty», «She looks too young to give an opinion», «I think she can’t close her mouth».

These are some of the comments that frequently appear in the content I publish. Their mission is to generate insecurity and try to ensure that women only inhabit private spaces, like our homes. I have noticed that the most aggressive comments on my account arise when I talk about machismo and national politics. In this scenario, aesthetic violence seeks to make us drop the camera and microphone. Therefore, to resist is to continue making us uncomfortable with our voices and bodies. The nonviolent resistance that I decided to do from the creation of content is to continue creating and talking with my community about violent situations, as in the video “The time they made fun of me for being a feminist and having a big mouth.”

Furthermore, it is key to recognize that beauty is a social construction and is defined by those who have power. Traditional media over time have reproduced the hegemonic paradigm of beauty and again we find the power of content creation on Tiktok by contesting narratives and showing diversity. The political dispute is cultural and generating material transformations also implies a process of transforming imaginaries.

However, this resistance must be accompanied by refuge in safe spaces, because that is where it is supported by emotions and digital strategies are implemented. Many times in the Creadoras Camp chat, support is requested to send positive comments on the video where the haters are writing from hatred. I have learned that comments help engagement, but there are always limits and tools can be used such as filtering comments, blocking accounts, reporting for inciting hatred, among others, all in order to build a safer community. A community that will support you like your neighborhood in the physical world.

Tiktok is my trench to share thoughts, agendas, questions. It is where I put my body and work, for me it is a new global village full of information and misinformation. So I will continue to dodge haters while reporting with a critical eye.

Astrid Torres

Journalist, filmmaker and content creator with a focus on human rights. His research and work focus on counterhegemonic studies from the cultural field.

Text published on June 28 with the support of FES

Translated by Damian Vasquez