Linda Y. Posso Gómez

Colombia is a country full of contrasts. More than half a century of armed conflicts which generated

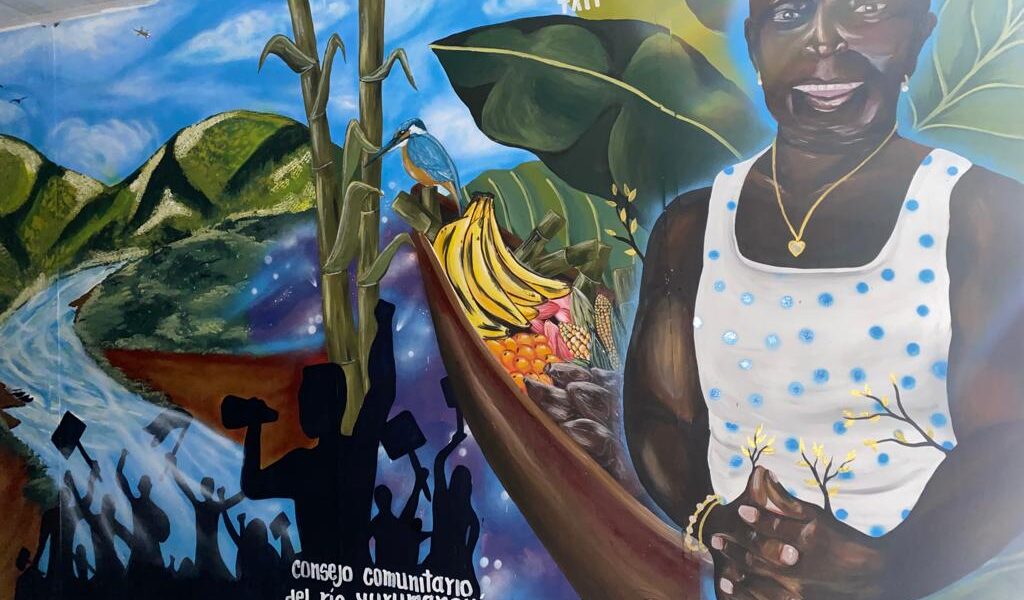

a shield in the heart of black communities of the Colombian Pacific. A shield of nonviolent resistance.

This is what has allowed for the black community of Yurumangui in the District of Buenaventura,

which is today a territory free of illicit crops and has become a benchmark in the country, to

think from their experience the praxis of peace in the post-conflict.

By the of the 90s, the war in Colombia had already penetrated the heart of the black communities in

the mid pacific zone. The arrival of armed actors meant death, anxiety and loss of autonomy for the

Black communities. With them, cultivation of illicit use it became an uncontrollable phenomenon

that ended breaking the social and cultural fabric in the territories where it spread. But Yurumangui

was the exception.

Yurumangui is a river, a community, an extended family. A territory made up of thirteen villages, which

are forms of rural territorial subdivision and are characterized by being small territories belonging to

a larger political administrative jurisdiction. The paths are located along the Yurumangui River, in

the rural area of the Buenaventura district, one of the most important ports of Colombian and Latin

America. This reality is seen by many as both an advantage and disadvantage, depending on who you

ask. On the one hand, for national trade, the geostrategic location of the port is vital in terms of exports

and imports. On the other hand, for the communities that inhabit in the territory, this reality has

systematically generated the violation of individual and collective rights.

From the end of the 20th century and the beginning to the 21st century, war began to come with

force and with it nonviolent resistance arose in Yarumangui, which although relatively new to the

phenomenon of conflict, has always been a life mandate for the communities. It is about the use of

practices, strategies and methods based on cultural and ancestral dynamics of the community at the

service of protection and self-protection against an external actor with a lot of power, in the

traditional sense of power. That is, with the ability to dominate through force, understanding of an

asymmetric relationship where one orders and the other obeys, or in Raymond Aron’s terms, which

has the ability to destroy.

When the illegal armed actors arrived in Yurumangui and the idea of coca cultivation as a form of

work, profit, and economic growth began to take hold, a context of uncertainty and concern was

generated. A precedent already existed, the Yurumanguiereño were closely aware of the reality of

the Naya river, a neighboring community permeated by illicit crops and in 2019 was considered the

territory with the highest prevalence of crops in the Valle del Cauca (one of the 32 departments in the

country). They had seen up close how this community had become divided, how they lost

autonomy in the face of armed actors and how there was a rupture in the social fabric. That, they

did not want.

For Yurumangui, community autonomy it clearly what prevails as the collective territory of black

communities. This is how, through the General Assembly, a territory was declared “free of illicit

crops, free of heavy mining and free of single crop farming”. However, this was not enough to

counteract the pressure of the illegal armed groups that in 2007 decided to plant twenty-seven hectares of coca

leaves, overriding the community’s mandates to not cultivate. Undoubtedly there was a lot of pressure

from the armed actors, death threats were daily life for those that decided to interfere. But, the

yurumanguiereño, as a community decided to develop a strategy of nonviolent resistance and

confront the power of the opponent.

They developed the campaign “I am a respectful yurumanguiereño: I do not plant, grow or consume

coca.” This campaign had a priority to counteract the actions of the violent. Around three hundred persons were

organized and mobilized to carry out days of manual eradication of the crops. The nonviolent action

took place for three days, a caravan of boats mobilized the population and was accompanied by a

constant dissemination of messages demanding for community autonomy, they made posters that

motivated community strengthening, rejected the incidence of illegal armed actors and the violation of

the right of territorial autonomy. In addition, during the manual eradication days, community pots were

made, a practice that reveals unity and strengthens the extended family relationships that

characterized the territory.

This generated serious threats to the female and male leaders. Opposing coca cultivation was seen

by many as an affront to the armed groups. The intimidation became constant and there was a

latent risk. However, the community decided to stick to its mandate and began to speak out

officially against the illicit crops. Their voice was heard not only locally, but in national and international

spaces. Despite the accusations and threats, the strategy set a precedent, marked a different course

not only for the community but for the country. In a county that is characterized as the largest

producer of cocaine in the word, there was a territory that was opposed to growing coca, which

despite having all the conditions of unsatisfied basic needs, strategic location, armed actors, and

adjoining communities cocaleros, they resisted cultivating. The community grew stronger.

Years later, new attempts to cultivate coca emerged, although there was already a solid leadership

that, from homes, schools and community centers, advocated to position the campaign “I am a

respectful Yurumanguiereño, I do not sow, I do not cultivate nor use coke.” This time it was not an

armed actor, it was an inhabitant though. Some say that it was regarding a foreigner. What is certain

is that a new movement for eradication was formed. The Yurumangui have made it clear that they will

carry out manual eradication as many times as necessary.

But the message was not only for the armed groups that wanted to enter the territory but also for

the national government that for many years has developed a policy of forced eradication and

fumigation with glyphosate. The message was accurate both ways. They did not want coca in them

territory because with it comes dispossession, the rupture of the social fabric, the loss of identity

and autonomy. Nor did they want forced interventions because it finishes with food sovereignty and

destroys the territory that is life itself.

What began as a campaign of nonviolent resistance, combining various methods of persuasion and

rejection, became a mandate for the community. In 2017, in Colombia, the magazine Semana

awarded the prize for “Best Leaders of Colombia” to the community of Yurumangui and they were

named Cultivators of hope.” Currently, this community continues to be a benchmark for advancing

organizational strengthening as key point for peacebuilding in the country.

Yurumangui does not know how long it will have to resist the violence, the crops and the various

threats that come to this territory. We trust in the new government’s commitment to total peace,

the idea of negotiating with all the fringe groups that operate in the territory. Meanwhile,

nonviolent resistance has been and will continue to be the way to build peace.

This article arises within the framework of the research work called “Buenaventura: A cradle of

resistance and peace building.” As an author, I recognize myself as a young, black, Bonaverense

woman.

Linda Y. Posso Gómez

Originally from Buenaventura, Colombia. Sociology. Master in International Relations, mention in

security and human rights.

Translated by Damian Vásquez