Margarita Sánchez

How about we revisit the concept of nonviolent resistance and nonviolent actions? I make this proposal being myself part of a long pacifist tradition. I suspect that concepts such as nonviolence and peace have been co-opted by hegemonic power structures. These are discourses that sometimes seem to be constructed to tame the efforts of anti-systemic resistance. When I allude to anti-systemic resistance, I am specifically referring to processes that seek to dismantle in one way or another the capitalist, racist, patriarchal, heteronormative systems. It seems that for an anti-systemic resistance to be recognized as being politically acceptable it must not have traces of violence.

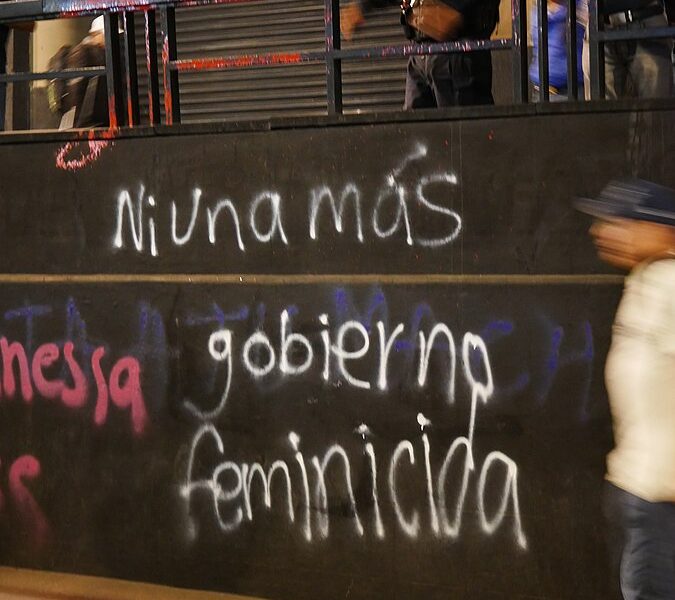

I wonder how we would describe the graffiti on iconic monuments in Mexico that occurred during various demonstrations demanding the state due to femicide violence or how we would call the beheading of statues of men with clearly racist and colonialist histories that occurred as part of global demonstrations to denounce racism? I heard many people, especially from hegemonic power structures, disqualify feminist marches for violent acts against national symbols or for confronting police forces. I have also heard people who invalidate the claims of anti-racist movements for the actions of beheading the statues of colonialist and racist men that are perpetuated in history, not only through monuments, but also in the names of streets, avenues, buildings, neighborhoods, among others.

It is not that we are calling for the use of violence by anti-systemic resistance movements, on the contrary, we wonder if the concept of nonviolence is used to disqualify the actions of some groups or movements. Or, in any case, what do we understand by violence in the context of systemic oppression? From my point of view, these actions of the anti-systemic movements, which some describe as violent, are expressions of pain and anger. These two feelings lead us not to be satisfied, to seek a change, to understand that what we are witnessing is not right, it is not fair. They are feelings that say that we do not accept the systemic violence of this world.

The violence that threatens the lives of people and beings that inhabit Pachamama, Gaia, those that systematically kill, are generated from structures and systems of oppression, even when it comes to apparent individual actions. Extreme individual violence is sustained in systems that, in one way or another, give permission and give way to these actions. States, large companies —legal and non-legal— claim decision-making power over the life and death of the people and beings that inhabit this Earth. This permission to decide who lives and who dies is what the Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe has called the new sovereignty or necropolitics. And that necropolitics is sustained by technologies of oppression such as racism or patriarchy. For example, the anthropologist Laura Rita Segato uses the concept of “ownership” to explain why femicides occur with the support of social and political structures. That “ownership” over the bodies of women —those that are read and/or defined as such— promoted by political and social institutions, is what gives permission to murder women. So, the decapitation of statues, the graffiti on national monuments are expressions of pain and anger in the face of systemic violence that is only possible from the structures of oppression.

Those who are precarious (Judith Butler), none (Eduardo Galeano) or subaltern subjects (Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak), have always resisted systems of oppression with or without political intent, that is, organized or not, through informal or formal actions. In this sense, nonviolence movements, or better still, movements that resist systemic violence, are much broader than those that we “officially” recognize.

In 2018, the American hemisphere witnessed an unprecedented phenomenon: hundreds and even thousands of people who lived in unacceptable conditions of violence and poverty in their countries of origin organized to come together to what from their perspective was the land where milk and honey flows (United States). Almost all came from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. The purpose of going in caravans was to have greater protection from the dangers of the journey and to defend oneself through solidarity among the vulnerable.

In 2021, a new caravan moved north. This time there were hundreds of Haitians. They had been waiting for a long time to be welcomed in southern countries, two years of waiting to receive a visa, an asylum recognition. The people started walking. They stayed trapped under the Río Grande bridge (Mexico-United States border). These caravans of people in search of safety are one of the most impressive nonviolent movements, or resistance to systemic violence, of our times. I do not think they intend to denounce the governments, however, their actions in search of new possibilities make them one of the forces that constantly question the political systems of the governments that administer the lands from which they come and expose to the governments that administer the lands that receive them or not. The caravans question the borders, they question the concept of security that is always built thinking of “the other” with the privileges granted by racist, colonial, patriarchal, heteronormative systems. They question the way in which resources are distributed and ultimately expose ourselves, those of us who are in a more comfortable or privileged situation. On the way there are thousands who die. The question will always be the one that the Judeo-American philosopher Judith Butler asks us: are those lives mournful or have we become accustomed to the inevitable losses?

The nonviolent resistances that we have witnessed in recent times have in many cases been very small efforts, but they are achieving significant changes in the way we understand our societies. They have multiple and horizontal leaderships. They have been articulated in various formal and informal ways with or without intention and serve to confront hegemonic powers. This should fill us with hope in the face of the strong wave of religious and political fundamentalisms that are the voices authorized by the structures of systemic oppression to block progress in the search for a full and abundant life for all the inhabitants of the Earth.

Margarita Sánchez de León

Queer theologian, originally from Puerto Rico. Professor of the Theological Community of Mexico, ordained pastor of the Metropolitan Church. She was the executive director of Amnesty International, Puerto Rico chapter, and has extensive experience working and taking action for human rights and LGBT rights through grassroots organizations and social movements.

Translated by Damian Vásquez